“We didn’t predict the weather forecast, we are just the porters.” This is a self-deprecating way to describe what we were doing. The current and forecast weather data is not created by us. Instead, we use a third-party API to get the data, process it, and show it to end users. However, there are several issues we face:

- What if the number of requests keeps increasing? That would mean we have to send more requests and pay more to the third party.

- What if the third party is out of service? We would have no data and be out of service as well.

- The weather forecast does not always change within a short period. Do we really need to request it from the third party so frequently?

Database caching research

By using a database to cache the data, we can reduce the number of requests sent to the third party and keep our data always available. This could completely solve our problem. During my research, I found that there are five popular strategies for implementation: cache-aside, read-through, write-through, write-back, and write-around. These strategies describe the relationship between the cache and the database, but they can also be applied when using a database (as a cache) in relation to a third-party API.

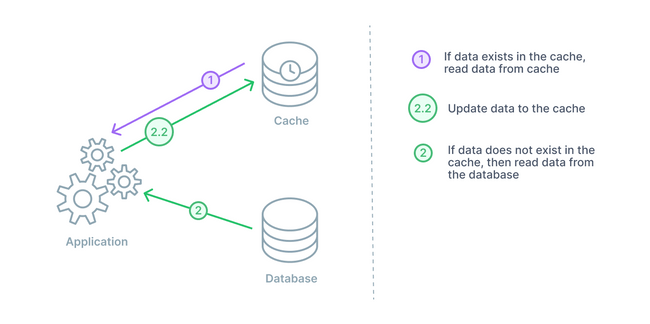

1. Cache-aside

In a cache-aside arrangement, the database cache sits next to the database. When the application requests data, it will check the cache first. If the cache has the data (a cache hit), then it will return it. If the cache does not have the data (a cache miss), then the application will query the database. The application then stores that data in the cache for any subsequent queries.

A cache-aside design is a good general purpose caching strategy. This strategy is particularly useful for applications with read-heavy workloads. This keeps frequently read data close at hand for the many incoming read requests. Two additional benefits stem from the cache being separated from the database. In the instance of a cache failure, the system relying on cache data can still go directly to the database. This provides some resiliency. Secondly, with the cache being separated, it can employ a different data model than that of the database.

On the other hand, the main drawback of a cache-aside strategy is the window being open for inconsistency from the database. Generally, any data being written will go to the database directly. Therefore, the cache may have a period of inconsistency with the primary database. There are different cache strategies to combat this depending on your needs.

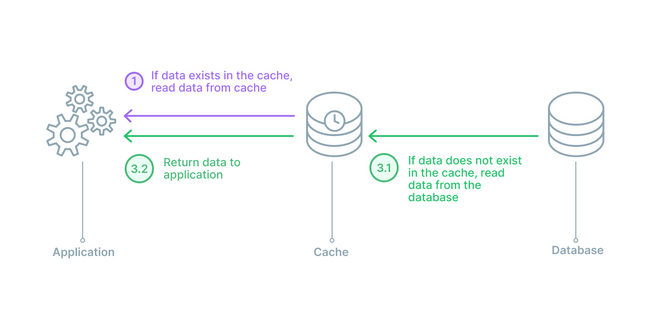

2. Read-through

In a read through cache arrangement, the cache sits between the application and the database. It can be envisioned like a straight line from application to database with the cache in the middle. In this strategy, the application will always speak with the cache for a read, and when there is a cache hit, the data is immediately returned. In the case of a cache miss, the cache will populate the missing data from the database and then return it to the application. For any data writes, the application will still go directly to the database.

Read-through caches are also good for read-heavy workloads. The main differences between read-through and cache-aside is that in a cache-aside strategy the application is responsible for fetching the data and populating the cache, while in a read-through setup, the logic is done by a library or some separate cache provider. A read-through setup is similar to a cache-aside in regards to potential data inconsistency between cache and database.

A read-through caching strategy also has the disadvantage of needing to go to the database to get the data anytime a new read request comes through. This data has never been cached before so therefore the data needs to be loaded. It is common for developers to mitigate this delay by ‘warming’ the cache by issuing likely to happen queries manually.

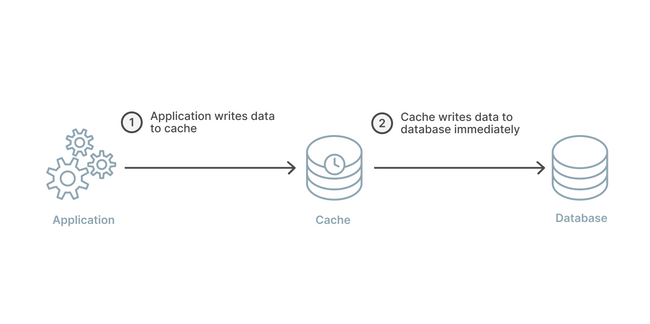

3. Write-through

A write-through caching strategy differs from the previously two mentioned because instead of writing data to the database, it will write to the cache first and the cache immediately writes to the database. The arrangement can still be visualized like the read-through strategy, in a straight line with the application in the middle.

The benefit to a write-through strategy is that the cache is ensured to have any written data and no new read will experience delay while the cache requests it from the main database. If solely making this arrangement, there is the big disadvantage of extra write latency because the action must go to the cache and then to the database. This should happen immediately, but there is still two writes occuring in succession.

The real benefit comes from pairing a write-through with a read-through cache. This strategy will adopt all the aforementioned benefits of the read-through caching strategy with the added benefit of removing the potential for data inconsistency.

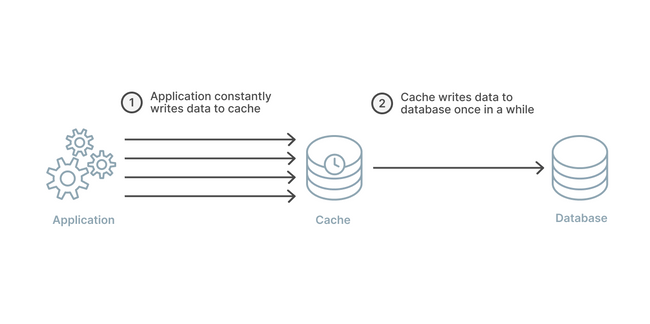

4. Write-back

Write-back works almost exactly the same as the write-through strategy except for one key detail. In a write-back strategy, the application again writes directly to the cache. However, the cache does not immediately write to the database, and it instead writes after a delay.

By writing to the database with a delay instead of immediately, the strain on the cache is reduced in a write-heavy workload. This makes a write-back, read-through combination good for mixed workloads. This pairing ensures that the most recently written data and accessed data is always present and accessible via the cache.

The delay in cache to database writes can improve overall write performance and if batching is supported then also a reduction in overall writes. This opens up the potential for some cost savings and overall workload reduction. However, in the case of a cache failure, this delay opens the door for possible data loss if the batch or delayed write to the database has not yet occurred.

5. Write-around

A write-around caching strategy will be combined with either a cache-aside or a read-through. In this arrangement, data is always written to the database and the data that is read goes to the cache. If there is a cache miss, then the application will read to the database and then update the cache for next time.

This particular strategy is going to be most performant in instances where data is only written once and not updated. The data is read very infrequently or not at all.

Cache implementation

In our case, we use the cache-aside policy to cache the data. Below is the code for our implementation,

# Try to fetch recent data (within 1 hour) from the cache table

cached = CityWeatherCurrent.objects.filter(

city_id=city_id,

created_at__gte=one_hour_ago

).order_by('-created_at').first()

if cached:

# Cache hit - return the cached data directly

...

return {

"id": int(city_id),

"cityname": city.cityname,

...

}

# Cache miss - fetch data from external API

response = requests.get(API_BASE_URL, params={

"id": city_id,

"APPID": APP_ID,

"units": "metric"

}, timeout=5)

data = response.json()

# Write the fetched data into the cache table for future use

CityWeatherCurrent.objects.create(

city_id=city_id,

...

)Some findings and thoughts

- A policy for removing legacy data needs to be considered.

- Data for popular cities can be preheated (loaded in advance).

- Stale data issues should be monitored and alerted.

- The availability of the third-party service is still important to the whole system.

- A lock is needed to avoid repeated cache writes (using Redis is recommended).